Interpreting Student Feedback

Responding to End-of-Semester Student Feedback on Course Experiences

At the end of each semester, students are asked to give feedback on their courses and instructors through the Student Feedback on Course Experiences survey. This feedback provides a great opportunity to grow as an instructor, but it is not a perfect measuring tool.

If you’re interested in a conversation about your reports, please schedule a consultation with a TLTC staff member. We’re happy to talk about your specific concerns and context.

Each item on the Student Feedback on Course Experiences survey is listed below. Expand each question to see tips for how to interpret and respond to each type of feedback.

As you read your feedback, keep in mind:

- These are students’ perspectives, not absolute truth

- Consider how you would reflect on each of these items yourself. What is your perspective?

- It’s important to think about context and consensus. Was this a typical semester? Are there patterns in the feedback from students? What other information did you gather about your course that you can integrate with the student feedback survey responses (e.g., peer evaluations, course design reviews).

- Mid-semester evaluations are often helpful for gathering information about why students are responding the way they are.

Course-Related Items

These questions appear once for each course.

Sharing a course curriculum map with your students can be helpful to show them how the activities and assignments relate to the course goals.

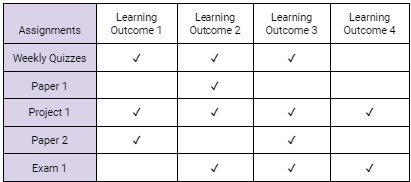

Example Course Curriculum Map:

Note: The purpose of the curriculum map is to show the alignment between the assignments and the learning outcomes. Specifically, which assignments are designed to test student mastery of each outcome.

Keep bringing up your learning outcomes and course goals with students throughout the course so that they understand how what you’re doing in class aligns. This could be stated next to assignments as they are listed on your syllabus, and/or discussed in class.

Ask yourself: does everything students spend lots of time on in class or on assignments relate to your learning outcomes and course goals? If they don’t, consult with your program to consider cutting an activity or adding a learning outcome.

Reflect on whether students had opportunities to practice the skills/thinking that they were asked to use on assessments. One way to do this is to consider each major assignment, and map on the instruction and practice opportunities students had before the deadline. If you find that students had ample opportunities to practice before each assignment was due, it may be helpful to be more explicit about naming the time to practice, and how it relates to assignments.

Calculate the full cost of the class, including books, printing, supplies, etc. Reflect on whether there are lower cost/free options of equal quality, and if there are any ways to save students money on the course.

Consider reading about Open Educational Resources and exploring less expensive options or alternatives.

There are several possibilities for low scores on this question, and it’s worth considering:

- Were students more advanced than usual? Did they already know what was being taught in the course?

- Did students really understand how far they had come since the beginning of the semester? Sometimes ungraded pre/post quizzes can help students see how far they have grown.

- Are you requiring the level of thought and perspectives appropriate for a course of this level?

- Did students have an opportunity to actively participate and engage with the material in order to think deeply about it?

Consider your students’ motivations for taking the course. Are they typically majors or non-majors? Is it a requirement or an elective? Particularly when students feel they are required to take a course, it can be helpful for student motivation to explain the relevance of the course to their future lives and careers.

It’s important to keep in mind that this is a question that taps into students’ perceptions of their learning, not an absolute measure of learning. Sometimes, we don’t realize how much we have learned until years later when the knowledge becomes more relevant in our careers or personal lives. Humans are notoriously bad at assessing the extent to which they have learned something without some assessment of that learning. If your students believe they aren’t learning a lot, it may be helpful to offer low-stakes assessments like check in quizzes in your class so students can document their growth over time.

It’s also possible for students to report that they haven’t learned a lot in the course because their prior knowledge was too advanced or too basic for the course they were in. Ungraded pretests can also help students self-select into the right course level for them that presents a reasonable amount of challenge.

eflect on whether the time students report spending is approximately what you expect, and whether it is aligned with the number of course credit hours students earn. Guidance varies across the university, but a general standard is that one credit hour should translate to 3 hours of student work. So a three-credit course should require about 9 hours of weekly work for students, including synchronous class meetings. If there is a misalignment, consider shifting the number or depth of assignments, and/or asking students the next semester about their progress in a mid-semester evaluation.

This question is helpful for understanding the motivation students have for taking your course and interpreting the other scores. There is no good or bad answer to this question.

Before reading your students’ qualitative comments, we suggest answering this question for yourself. What were things that you intentionally included to enhance your students’ learning? Did you make those choices explicit to students? Where there things about the course or instruction that you would want to change before you teach it next time? It can be helpful to see where you agree and disagree with students before seeing their suggestions.

For both open-ended questions, look for themes where multiple students provide similar feedback, and focus on actionable suggestions. If you’d like to talk through any student comments, please reach out to the TLTC.

Instructor-Related Items

These questions will appear once for each instructor in the course. Instructors do not see the results for other instructors in the course.

Consider the type of feedback (written, verbal, scores, etc) you are providing to your students. Are you providing clear suggestions so students know how they can improve their work over time?

Grading can take a long time, and it’s important to structure your assignment due dates so that it’s possible for you to give back grades and feedback before the next assignment is due. Reflect on whether that was possible for you this semester, and if it wasn’t, consider reducing your grading burden, spreading it out over longer periods of time, or requesting additional capacity like a TA or AMP. You can also consider ways to make your grading more efficient, such as auto-graded quizzes in ELMS.

Grading criteria can often take the form of a detailed rubric, but could also be part of the assignment description. It’s important for students to know what are the most important elements of the assignment before they turn in their work. If you have already provided detailed criteria in advance, consider asking students to grade their own work with the rubric before they submit it. This way, students will be required to engage deeply with the criteria before they turn in the assignment.

ELMS can be a very helpful tool for course communication about assignments. Make sure students are aware of major deadlines in the first two weeks of class, before the end of the add/drop period. It can be very helpful for student engagement if they understand the why and the what of the assignment. If some ambiguity is important for the nature of the assignment, that’s completely fine. We suggest communicating that you are aware of the ambiguity, that it’s an intentional choice, and why it’s an important part of the assignment.

This is a tried and true method of helping students understand new information. Scaffolding new content onto prior knowledge requires that instructors have some sense of what students already know, which can be helped by a pre-quiz. Instructors can connect new information onto prior coursework, or use metaphors or stories to help students understand new concepts.

This question is meant to assess one dimension of course climate. When students feel that they belong in the class, they are more likely to engage with the material, ask questions, and work hard. If this is low, the open-ended qualitative comments can often provide some explanation. A few ideas to include in your teaching practices would be learning your students’ names, creating a set of course norms, sharing your pronouns, and explaining to your students that you care about their mastery of the content.

Although not everyone will necessarily excel in every class, this question is about whether students felt that the instructor believed that anyone who qualified for the class (was accepted to UMD, completed the prerequisite courses necessary to take the class) could potentially succeed given effort. If the responses to this question are low, reflect on the starting point of the class - is it aligned with any prior coursework that’s required? Is it too hard or too easy for most students taking the class? Also consider any messages that you’re giving the students about whether you believe that they can succeed.

This is also a question about the students’ belief that the instructor cares about whether they learn the material, which is a strong predictor of student engagement and success. Consider how often you encourage your students, or talk to them about the relevance and importance of the course content.

This is a general student satisfaction question, so it’s a bit hard to understand why it might be low by itself. Instead, look at the other questions and open responses to see if there are any patterns about why students are or are not generally satisfied with the course.

Teaching Assistant-Related Items

These questions will appear once for each TA in the course. TAs do not see the results for other TAs in the course. Instructors see TA results for all TAs in their course. These questions are nearly the same as some of the course-related and instructor-related questions above.

Consider the type of feedback (written, verbal, scores, etc) you are providing to your students. Are you providing clear suggestions so students know how they can improve their work over time?

This is a tried and true method of helping students understand new information. Scaffolding new content onto prior knowledge requires that instructors have some sense of what students already know, which can be helped by a pre-quiz. Instructors can connect new information onto prior coursework, or use metaphors or stories to help students understand new concepts.

This question is meant to assess one dimension of course climate. When students feel that they belong in the class, they are more likely to engage with the material, ask questions, and work hard. If this is low, the open-ended qualitative comments can often provide some explanation. A few ideas to include in your teaching practices would be learning your students’ names, creating a set of course norms, sharing your pronouns, and explaining to your students that you care about their mastery of the content.

Although not everyone will necessarily excel in every class, this question is about whether students felt that the instructor believed that anyone who qualified for the class (was accepted to UMD, completed the prerequisite courses necessary to take the class) could potentially succeed given effort. If the responses to this question are low, reflect on the starting point of the class - is it aligned with any prior coursework that’s required? Is it too hard or too easy for most students taking the class? Also consider any messages that you’re giving the students about whether you believe that they can succeed.

These two questions reflect general student satisfaction, so it’s a bit hard to understand why it might be low by itself. Instead, look at the other questions and open responses to see if there are any patterns about why students are or are not generally satisfied with the course.

For qualitative, open-ended questions, look for themes where multiple students provide similar feedback, and focus on actionable suggestions. If you’d like to talk through any student comments, please reach out to the TLTC.